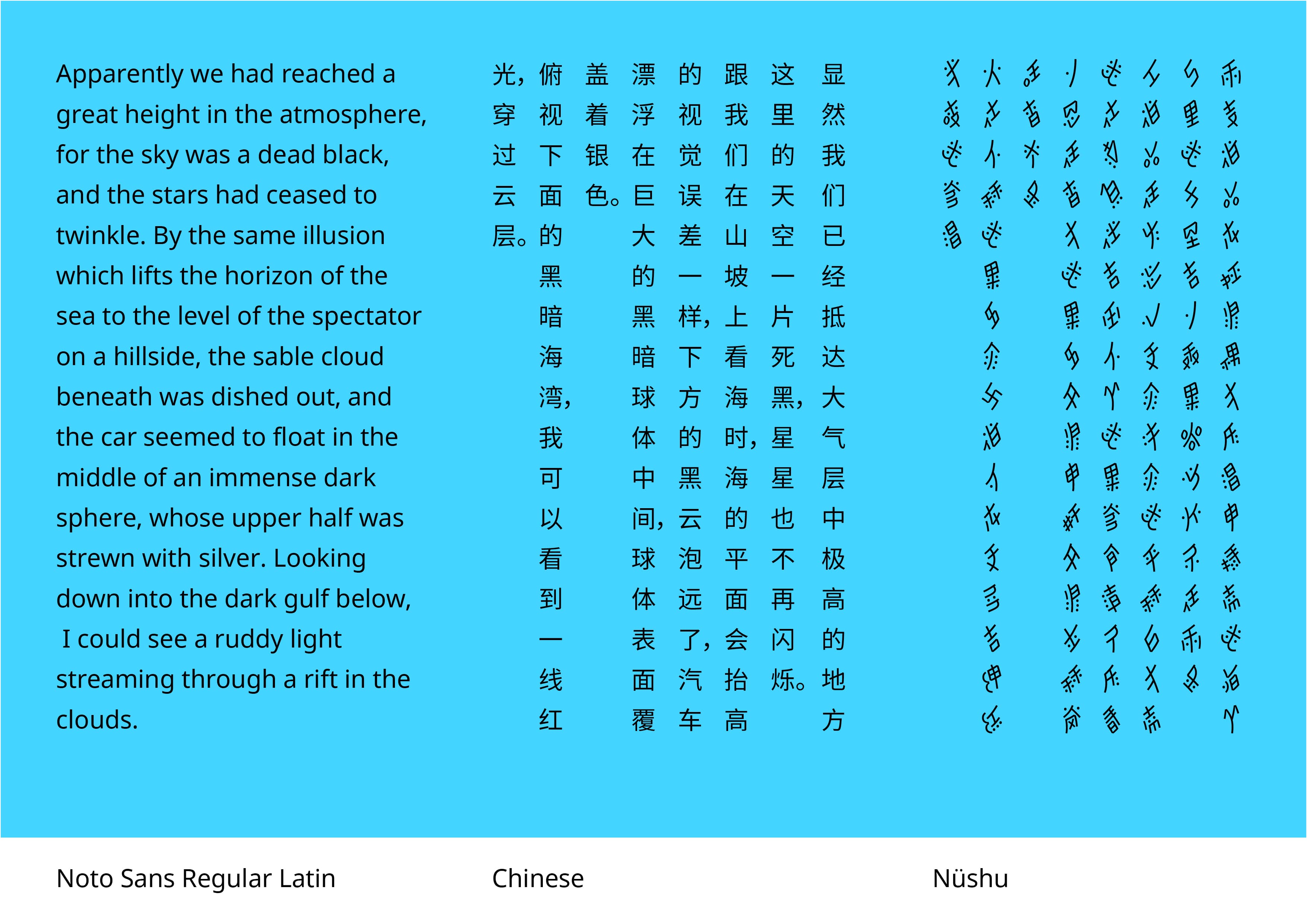

About Nüshu script and Noto Sans Nüshu

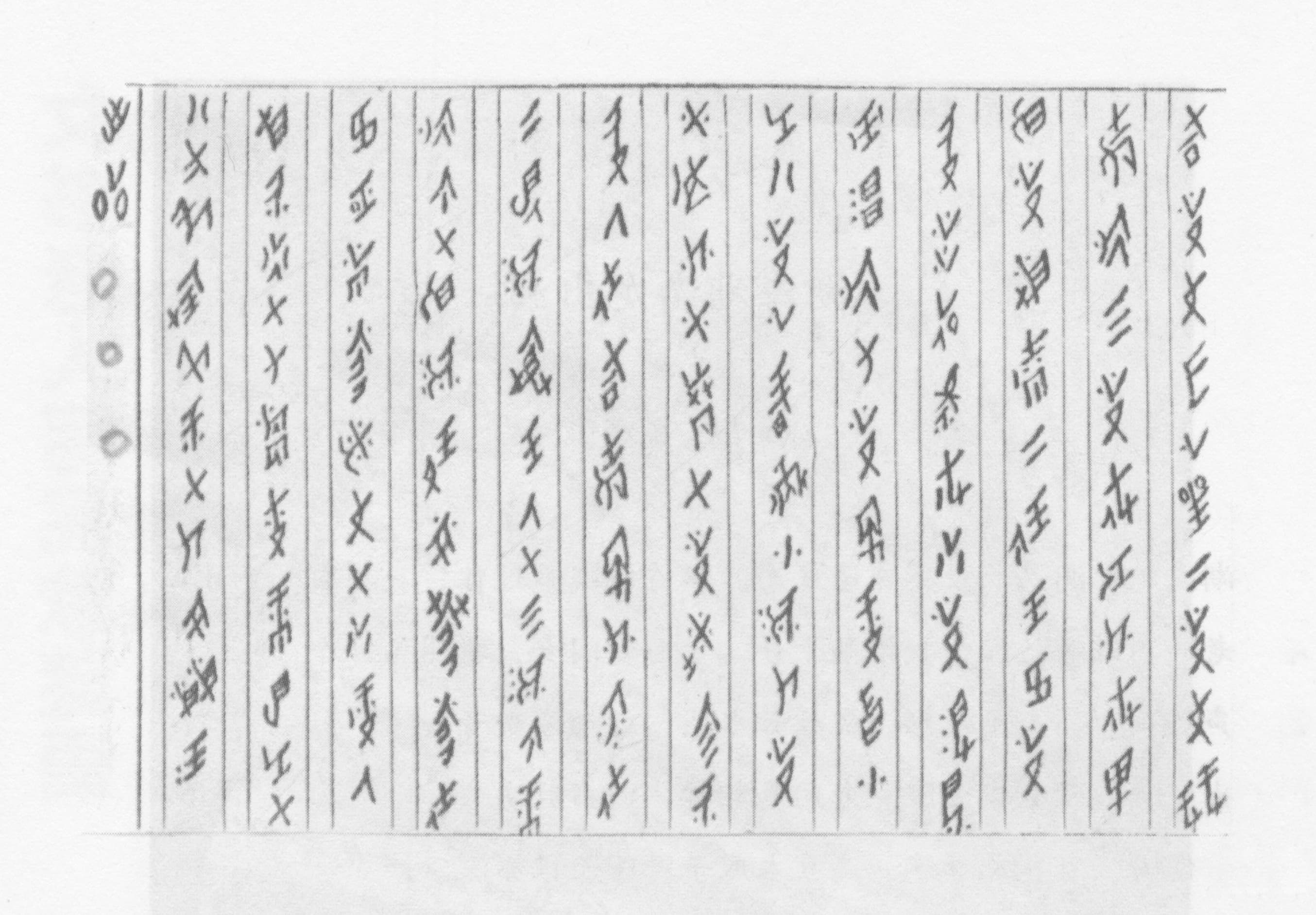

一岁女,手上珠 (One year girl, hands with pearl) by Gao Yinxian 高银仙 (1902–1990)

一岁女,手上珠 (One year girl, hands with pearl) by Gao Yinxian 高银仙 (1902–1990)

reading time: 15min

note: to avoid any confusion in words meaning, I will refer here : Chinese as Chinese spoken language. Hanzi as Chinese written characters (汉字). Nüshu as Nüshu script. Nüshu script as it is sounds redundant, as Nü (where the ü is pronounced like a French [u]) means ‘woman’ (女), and shū (书 - meaning more commonly ‘book’ but also ‘script’) stands for script already. Tuhua as local dialects (more explanations further below).

Introduction

In these modern times, literacy is something that we would take for granted, and for (almost) everyone across the globe. All along human history, writing systems play an essential role to its evolution. The knowledge of writing and reading is something that we imagine accessible to all in a utopic world, with no barriers, bringing societies further and better… But obviously and unfortunately, it hasn’t been this way. There must have been solutions through the ages, around the world, created and developed out of a practical need, but very few of them come to the general knowledge, reach our times, or are under the spotlight.

Until very recently though, this happened to one of them, on its almost-extinct moment: Nüshu writing system. It is a one of its kind example of a solution brought to life by self-educated people when academic education were not allowed to them because of both social an gender separation. This script’s existence demonstrates a solution to bypass a barrier with peace, and transform it into a way to elevate the users on their own with no foreign help or influence.

01. What and Where

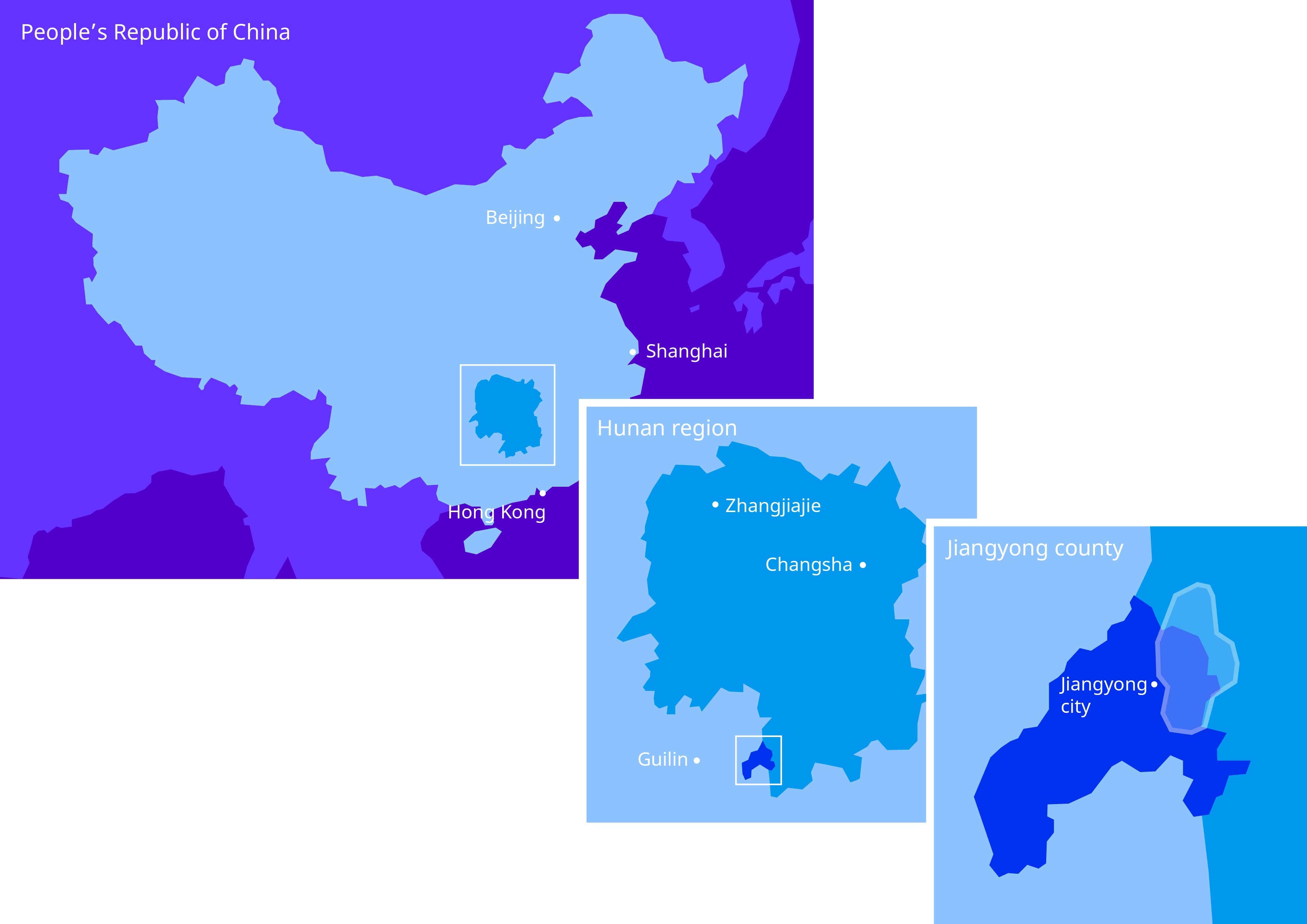

Nüshu is the only writing system developed and used exclusively by women in History in the world (as we know it so far… no one knows what is still awaiting to be discovered…) in the South East region of Hunan (湖南省) in China.

Description of Nüshu, as part of the 12.0 update of the Unicode Standard: “Nüshu is a siniform* script devised by and for women to write the local Chinese dialect of south eastern Hunan province, China. Nüshu is based on Chinese Han characters. Unlike Chinese, the characters typically denote the phonetic value of syllables. Less often Nüshu characters are used as ideographs. Although very few fluent Nüshu users were alive in the late twentieth century, the script has drawn national and international attention, leading to the study and preservation of the script.” (The Unicode Standard, version 12.0 - Core Specification - Chapter 18, East Asia, p.742, March 2019) *siniform: writing system that is based on or influenced by Chinese writing system.

This unique writing system lives in the remote areas of the province of Hunan, more precisely within the district of Jiangyong (江永县). The closest large city is Guilin (桂林), famous for its particular high mountains specific to the region. Jiangyong county spreads on about 1600 km², which a bit larger than the Greater London (1500 km²) but with a much fewer population (about 240,000 in 2015) with two main ethnic groups: Han and Yao. 1

note: even nowadays the disctrict of Jiangyong is still apart from the rest of the country, hard to reach, with regional trains, few train stations, and very reduced taxi service… as the only people moving around are ones living there.)

One of the many villages in the region, Shang Gan Tang 上甘棠,with over 1100 years of history.

One of the many villages in the region, Shang Gan Tang 上甘棠,with over 1100 years of history.

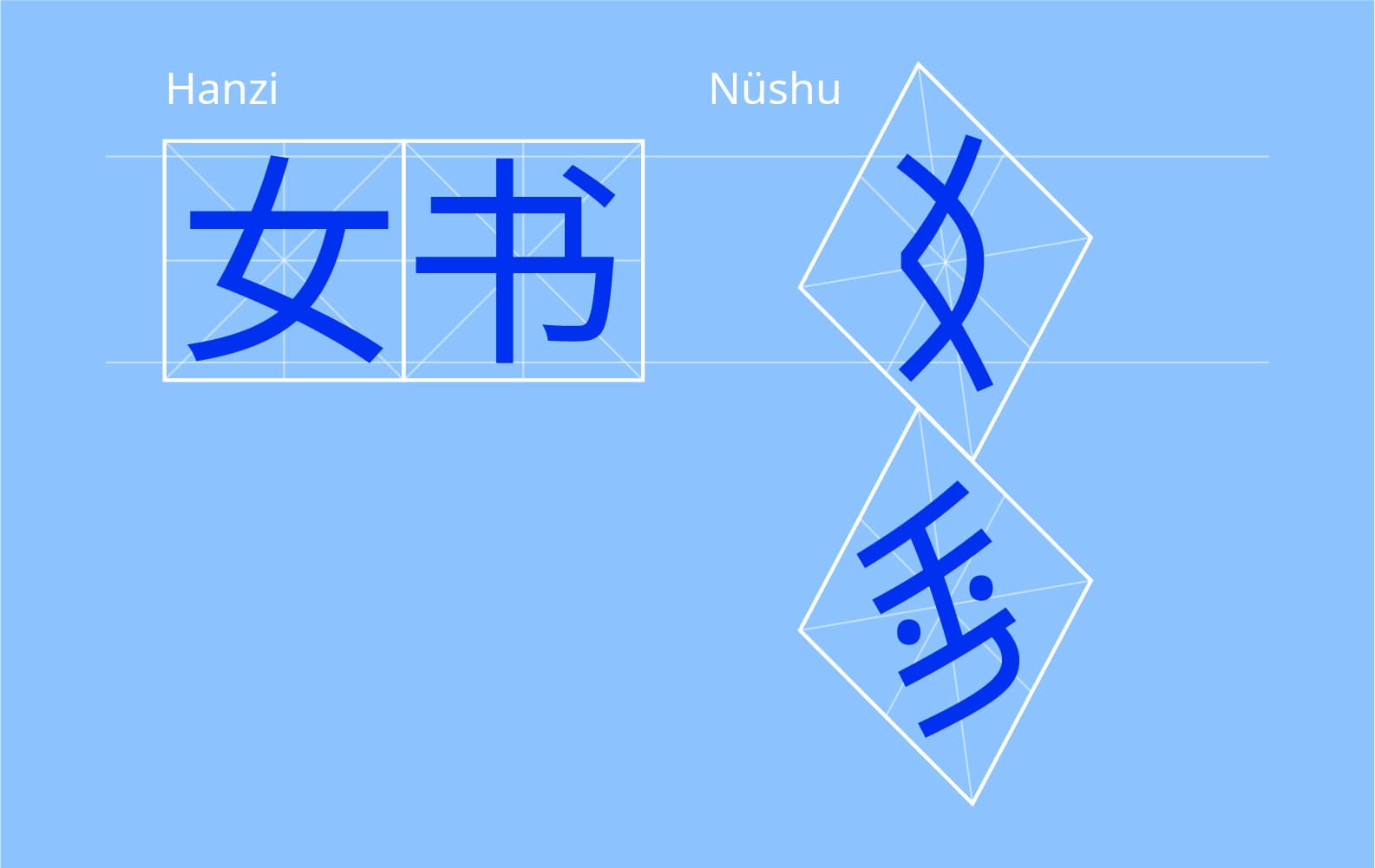

Nüshu is the phonetic transcription of 女书 in Chinese, which literally means ‘woman’ for 女 and ‘script’ or ‘writing’ for 书 (although it means ‘book’ more often). Just like when we speak of Lishu (隶书) for Clerical script, Kaishu (楷书) for Regular script or Caoshu (草书) for Cursive script.

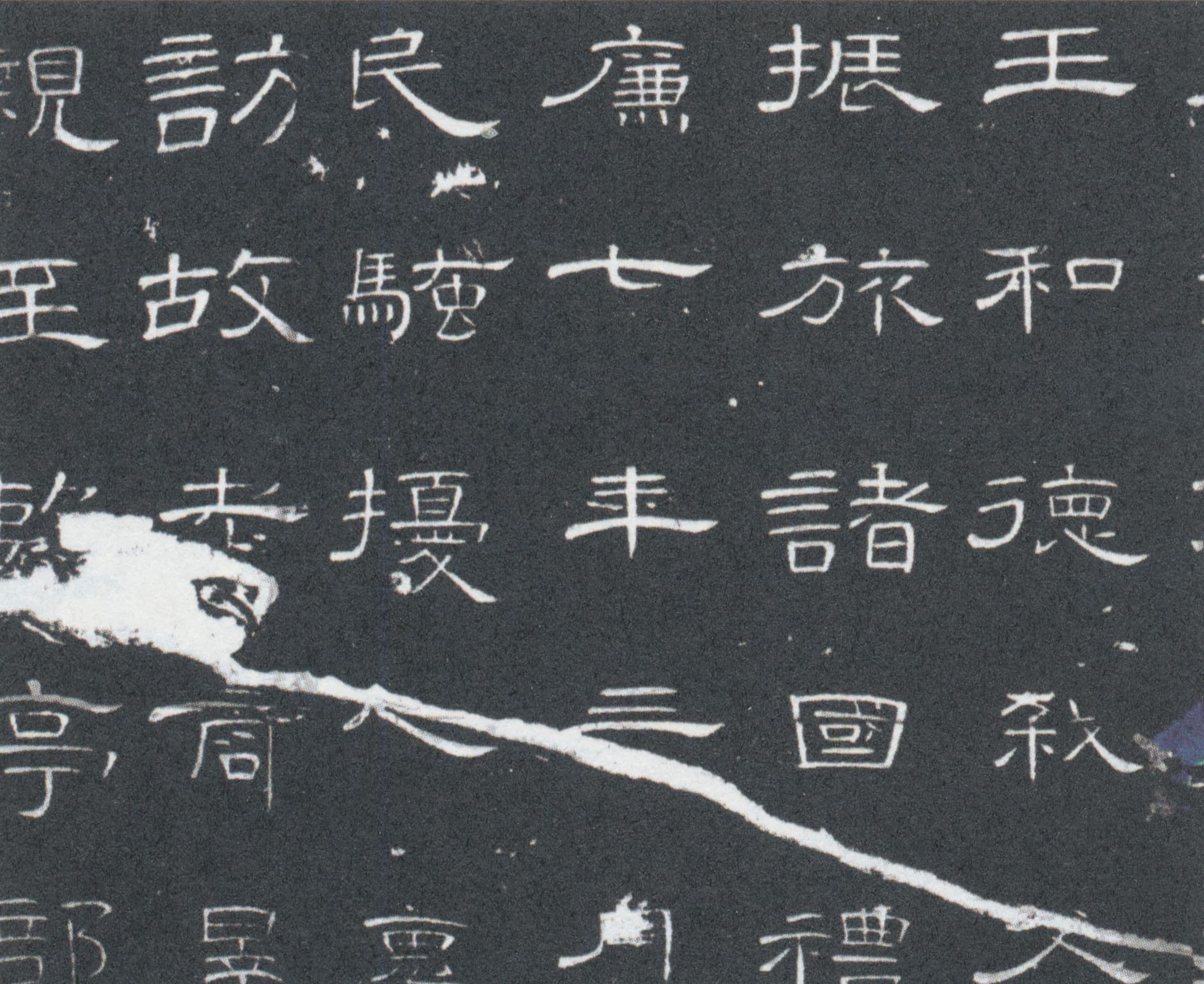

Lishu sample on Cao Quan Stele 曹全碑, from the Beilin Museum collection in Xi’an (碑林, 西安)

Lishu sample on Cao Quan Stele 曹全碑, from the Beilin Museum collection in Xi’an (碑林, 西安)

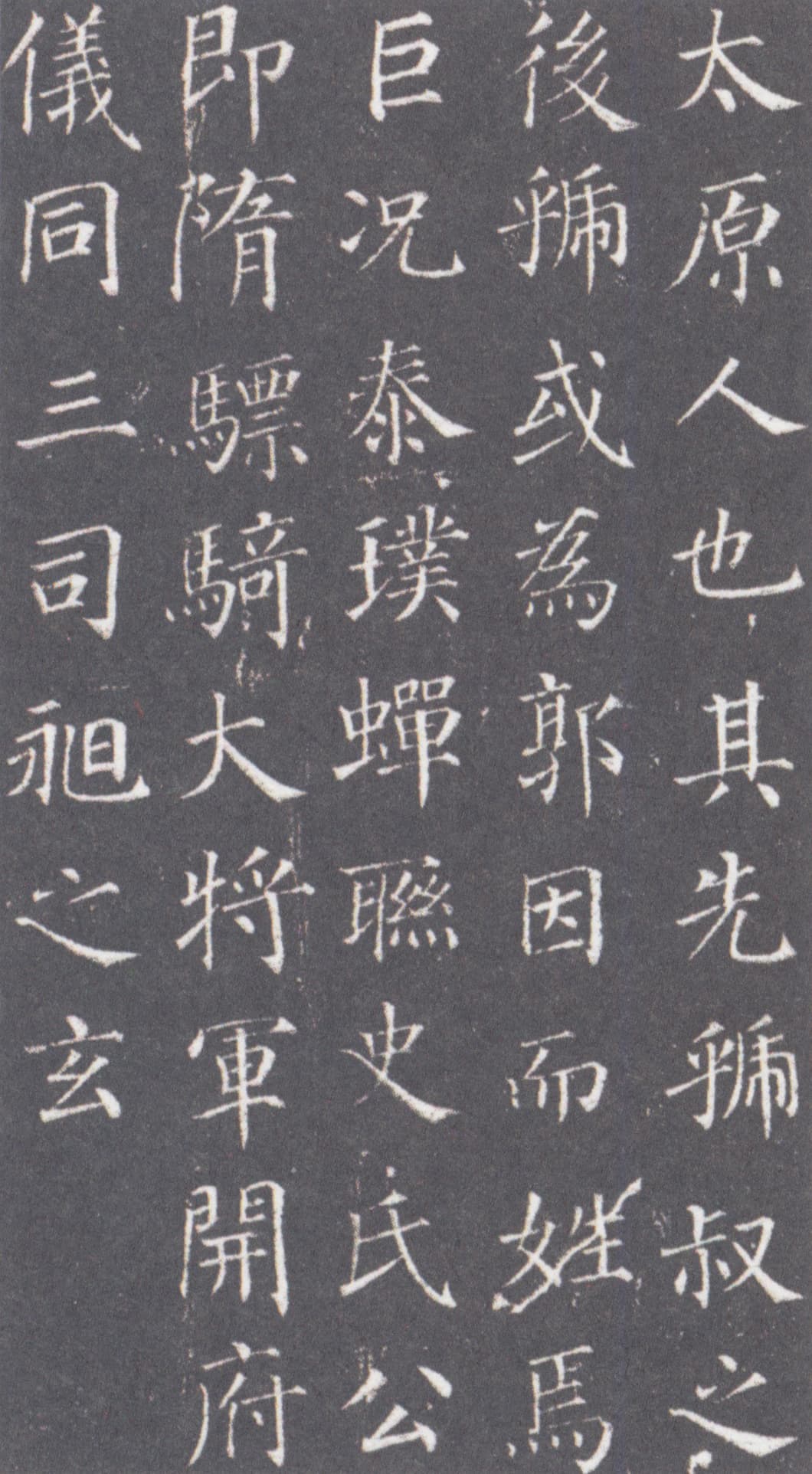

Kaishu sample, calligraphy by Yan Zhenqing 颜真卿 (709–784)

Kaishu sample, calligraphy by Yan Zhenqing 颜真卿 (709–784)

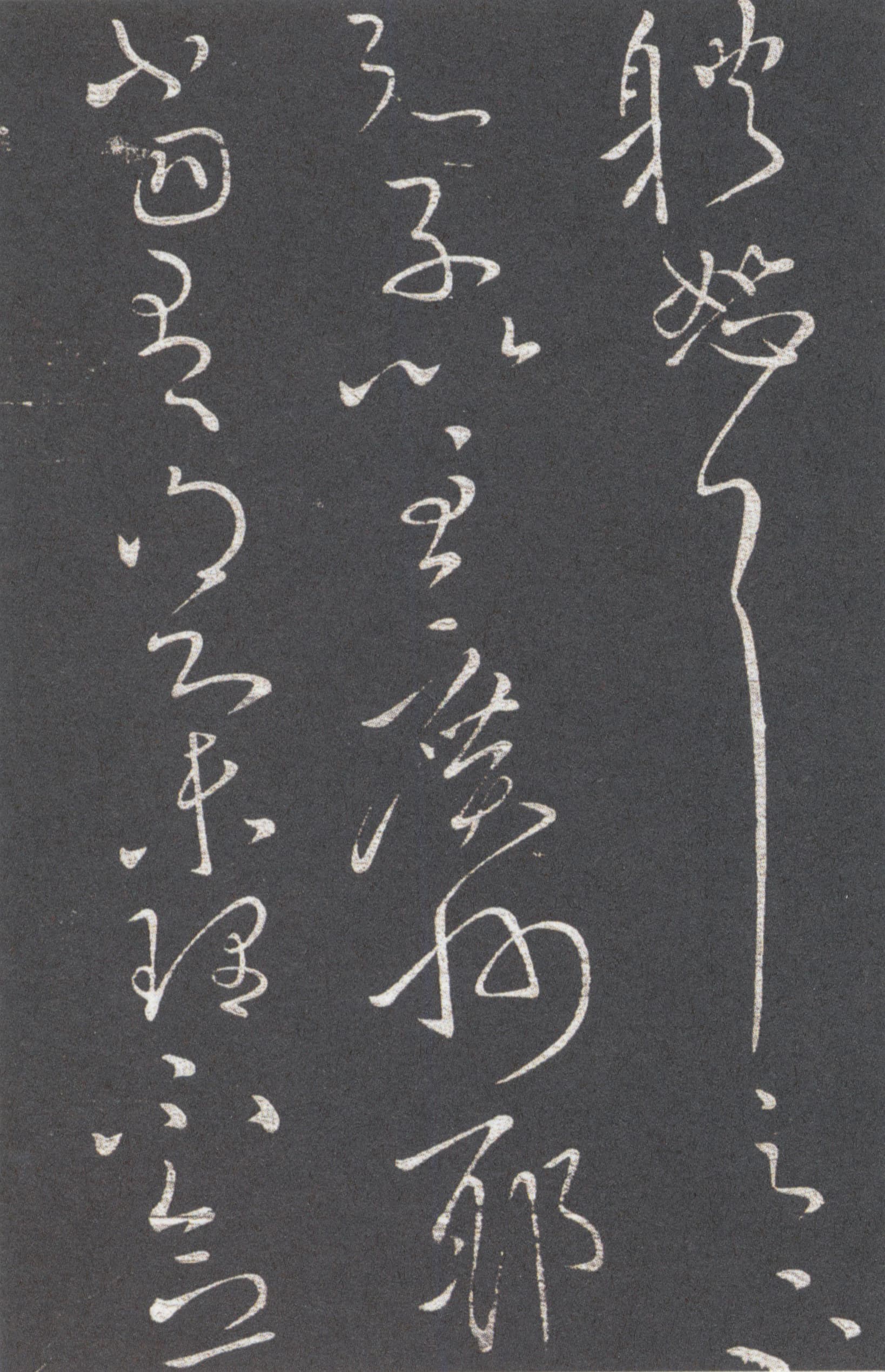

Caoshu sample, calligraphy by Wang Xianzhi (344–386)

Caoshu sample, calligraphy by Wang Xianzhi (344–386)

These examples show different calligraphic styles of a same script: Hanzi. Nüshu is a different script, strongly related to Chinese and to Hanzi.

note: Nüshu is called “Mosquito legs script” (蚊脚字) by the locals, while Nüshu is a denomination given to the script by academics.

Nüshu is not to be put in the same basket as the other calligraphy scripts, as it is not the visual transcription of Chinese language (so to speak), but one of the many local dialects in the area shown on the map above. The ‘s’ stands for the dialects put together, called Tuhua by the locals (土话, literally ‘land language’), spoken by the inhabitants (both women and men) of many villages, towns and cities in Jiangyong county.

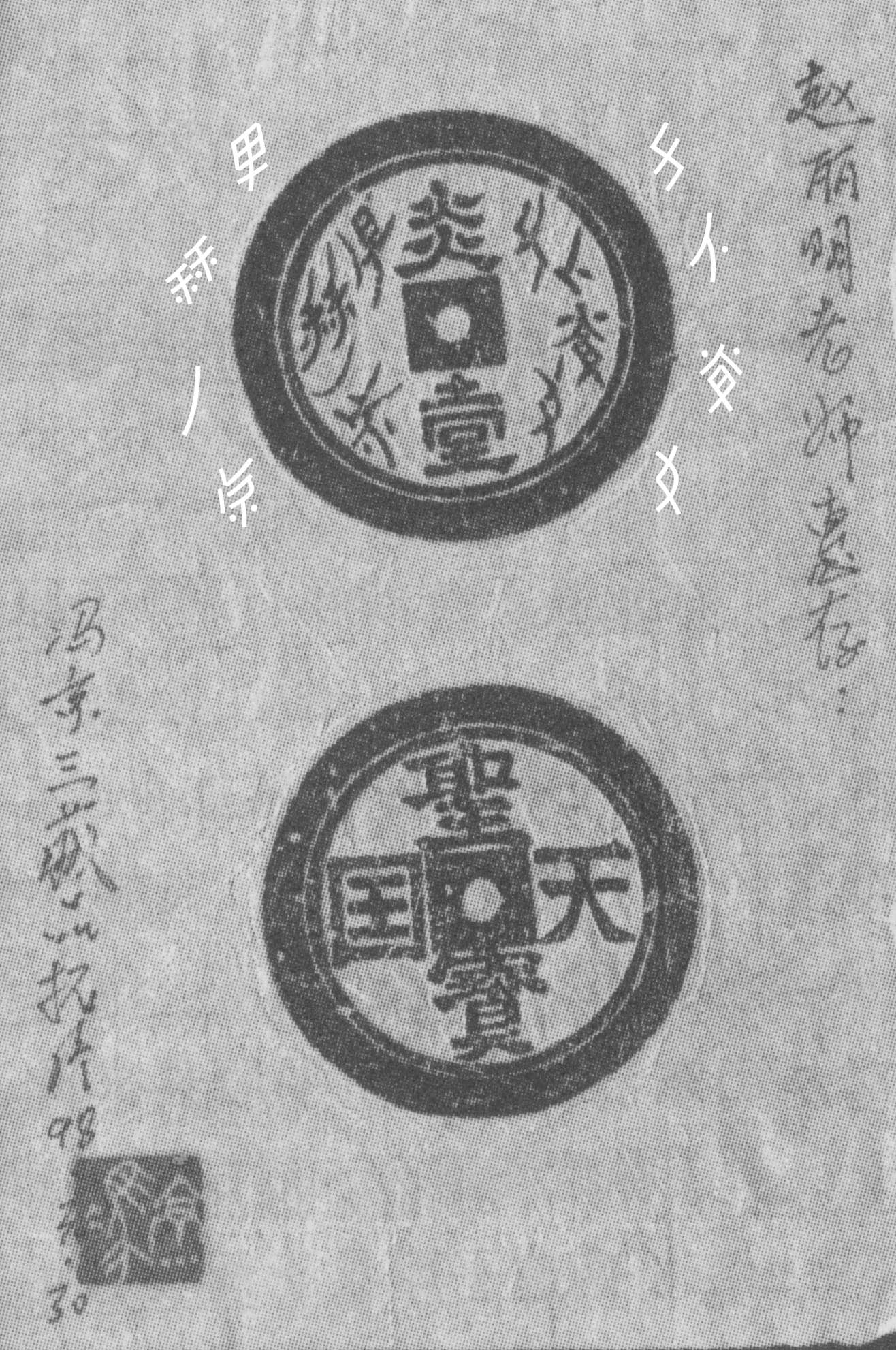

02. When

Even until nowadays it is hard to determine with certainty a date of origins for Nüshu, as there are very few old documents with this script or traces of its beginnings remaining (see in Chapter 06. How is it used to know why). But, it is said by most (serious) research that Nüshu finds its origins around the 9th century, during the beginning of Song dynasty (960–1279) from the oldest still existing documents or more recent ones mentioning Nüshu. Most of the documents and artefacts with Nüshu are dated from Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties, kept in Hunan Museum in Changsha. Bronze coins dated from Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (太平天国) era (1851–1864) has been discovered in 1993 in Nanjing (much further North to Jiangyong) with Nüshu characters on one side saying “women under the sky, sisters of one family” (天下妇女,姊妹一家). It is the oldest artefact found with Nüshu characters so far.

Bronze coin imprint with Nüshu correspondence, courtesy of Pr Zhao Liming 赵丽明

Bronze coin imprint with Nüshu correspondence, courtesy of Pr Zhao Liming 赵丽明

03. Why

In a feudal China, women were not allowed to read or write (Hanzi), a privilege given to the imperial family, nobility, administration and academics (which are exclusively men, apart from a handful of high rank women in the imperial family…). Literacy in China was at very low rate, for both men and women (literacy rates for women was very likely even lower than for men) until the 1950’s only! (see China’s Long — but Uneven — March to Literacy by Ted Plafker, New York Times, 2001).

In remote regions hardly accessible like Jiangyong in Hunan, exchanges of informations were rare, as moving to one village to another could take days if not weeks. Women in these rural areas were put away from society, left “only” in charge of the household chores and children, cut-off from any activities or events outside of their villages.

Once a women is wed (to a husband from another village), she would have to move to the husband’s family, which means leaving her own family, friends and birthplace. Women in Jiangyong didn’t know that much about outside world’s activity or news (and didn’t care much about it), but needed to keep contact with their loved ones.

Family and friendship are very cherished bonds, going from mother and daughters to sisters, cousins, etc… They have a tradition that can be called “sworn sisters” (结拜姊妹), like a best friend bond, an officially recognized relationship in the area, between two girls from different families allowing to freely move from one place to another without a male tutor (a widely spread rule in the patriarchal system).

In this context, women created in their parallel world a creative way full of practical sense to communicate between each other despite distances. They kept the script evolving through times, using it in many ways and ended up creating a culture of their own, aside the culture of men. This script is an wonderful example of creativity resulting from a social separation between men and women, and at the same time a strong solution to a problem: a missing connexion with cherished people and more. It shows also the character of the women who created, developed and used, still use nowadays, cultivating a strong personality with pride and calling themselves ‘gentlemen ladies’ (君子女) who have attitude, self-cultivation, spirit and interest (气质,修养,性情,志趣).

04. The look

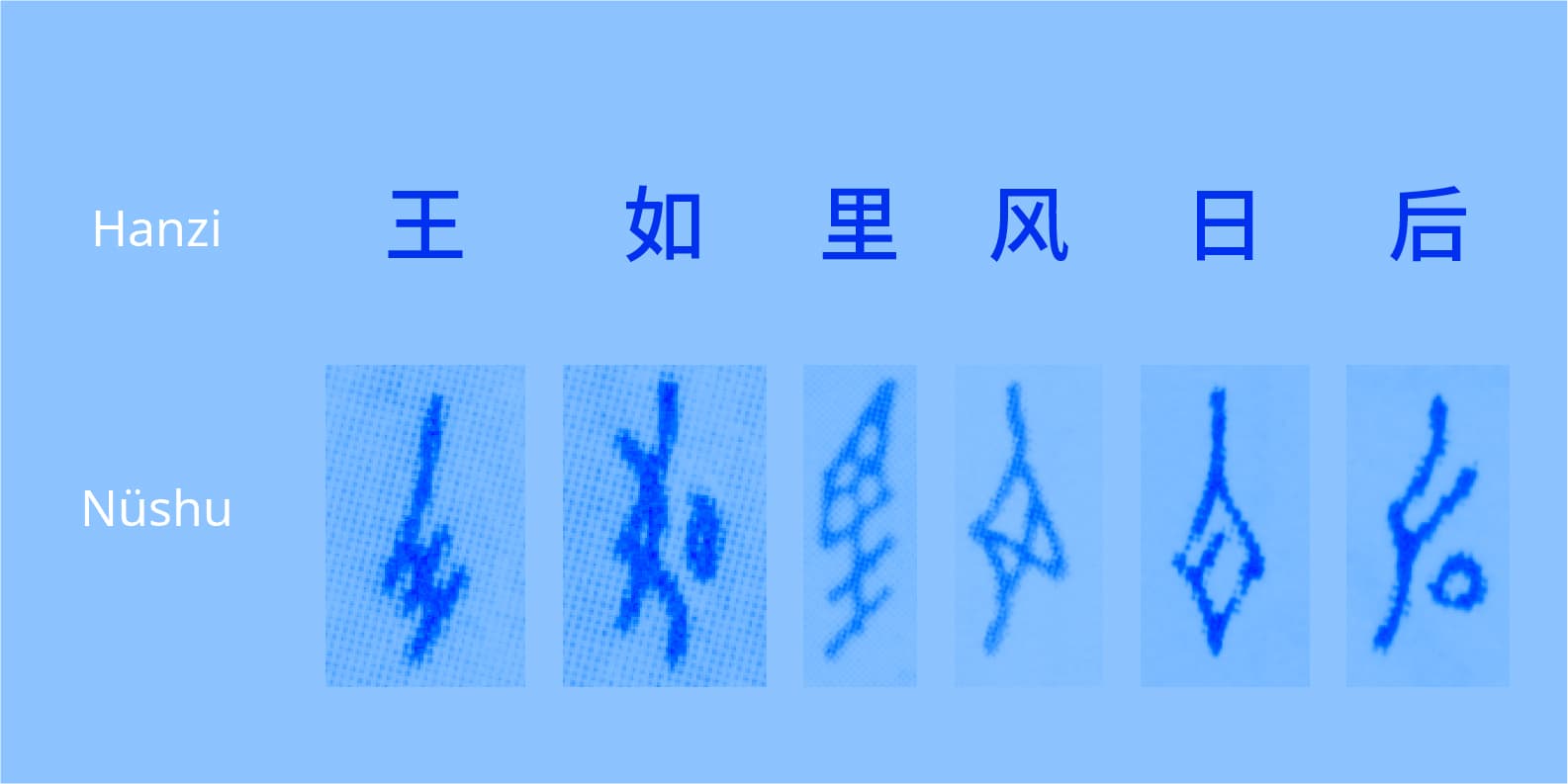

The mysterious look of the script for people unfamiliar with it created stories and legends or various degrees of craziness (language of women spies, witches, language from gods or supernatural beings …). But, more seriously, it is obvious that women who created and developed Nüshu got inspiration from Hanzi shapes and features (they used what they could see around them). Many Nüshu characters are even sort of distorted Hanzi characters, along with many other non-Hanzi related glyphs at all.

Top and bottom glyphs are strongly related in shapes, also for some situations related in sound and meaning

Top and bottom glyphs are strongly related in shapes, also for some situations related in sound and meaning

While Hanzi has a relatively large panel of strokes and shapes as elements of construction, several stroke directions and contrast given by the calligraphy brush, Nüshu is much more simpler (in a way). It has no strictly vertical or horizontal strokes, only curvy diagonals and lines (even the circles are made of two curves), mostly turned towards left, no punctuation, no serifs and no contrast (at least in its original version - as I had the possiblity to choose between working on Noto Sans or Serif for the Nüshu part, the Sans version seems the most relevant to start with and closest to the script itself).

Stroke directions in Hanzi can go in all directions, while for Nüshu it is (mostly) curves towards left and bottom

Stroke directions in Hanzi can go in all directions, while for Nüshu it is (mostly) curves towards left and bottom

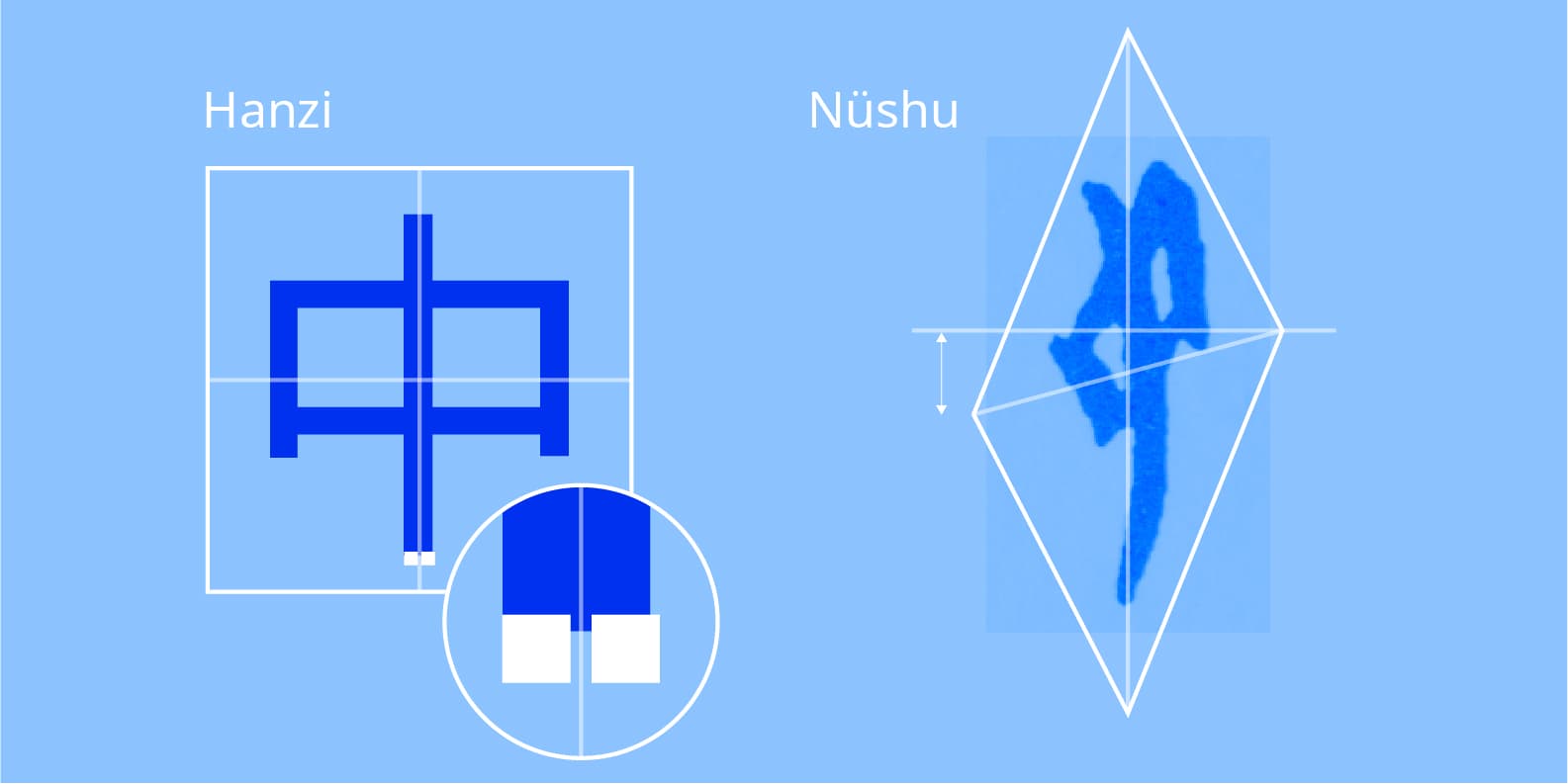

The characters in Nüshu are written and read vertically, then from right to left just like traditional Chinese texts. With Hanzi characters, one of the prominent rule besides balance of weights and white space is having the left side heavier than the right side (左重右轻 - ‘left heavy right light’). For Nüshu characters, balance is also a main point of focus, but the difference is their diamond shape general form and the rule of having the left side lower than the right side (右高左底 - ‘right high left low’).

This is a frame for Nüshu not to be taken by the letter, but it shows its general form…

This is a frame for Nüshu not to be taken by the letter, but it shows its general form…

Their overall proportions are quite elongated, much narrower than Hanzi characters. To keep the same level of legibility when set aside Latin letters or even Hanzi characters, they would go beyond both top and bottom heights.

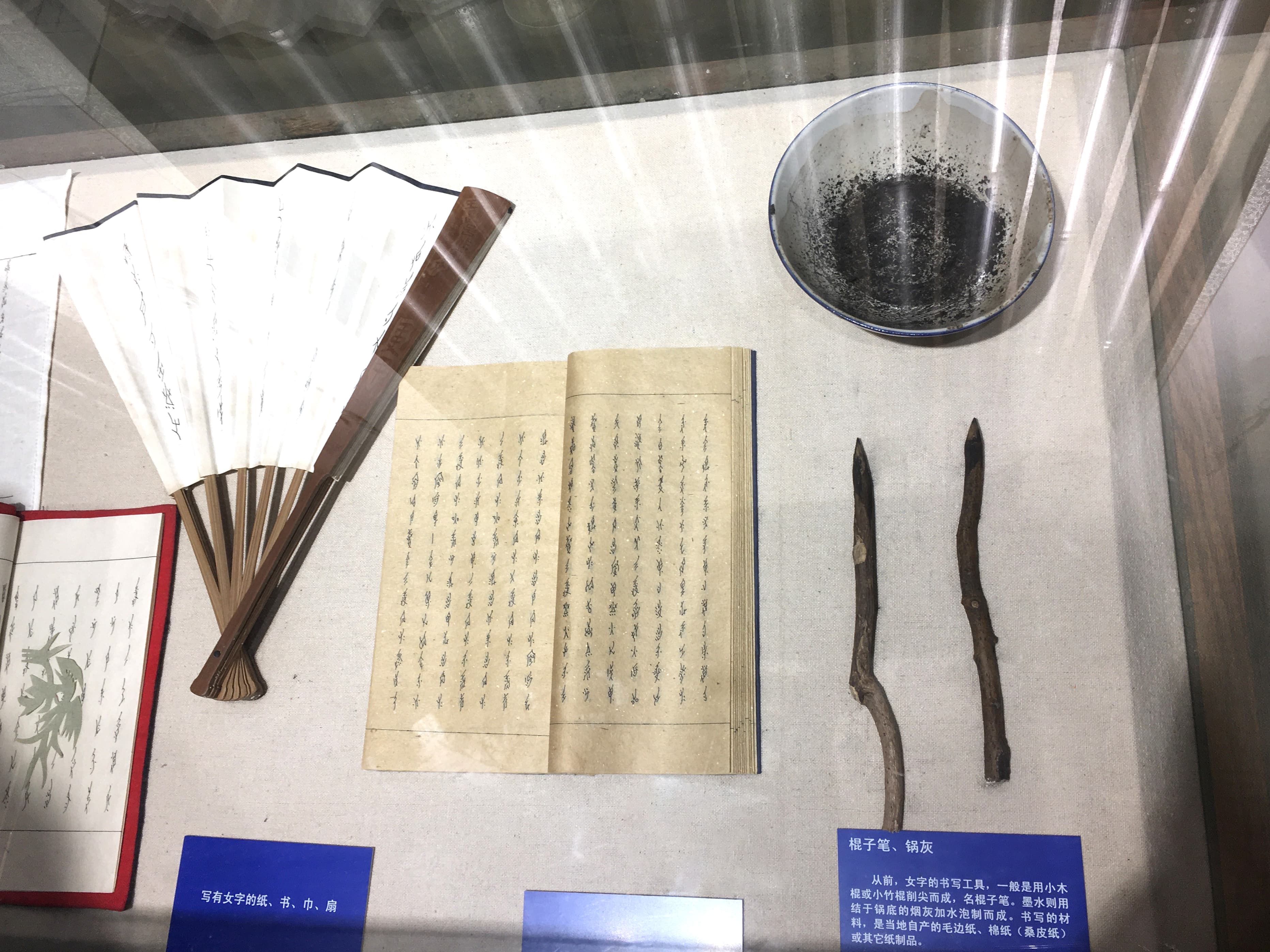

The elongated proportions of Nüshu characters is in itself a result of a women-men separation. For Hanzi calligraphy, there are the Four Treasures of the Study (文房四宝), calligrapher’s four essential items: brush, ink, paper and inkstone. All these put on a table, also mostly especially designed for calligraphy. These were “men’s realm”, therefore not allowed to women. They had to find other tools for Nüshu usage, and apart of paper or booklets, they created their own Treasures: wood or bamboo stick as pen, ash from wok pans bottom as ink, paper (also cloths, fans, booklets…) and their thighs as table.

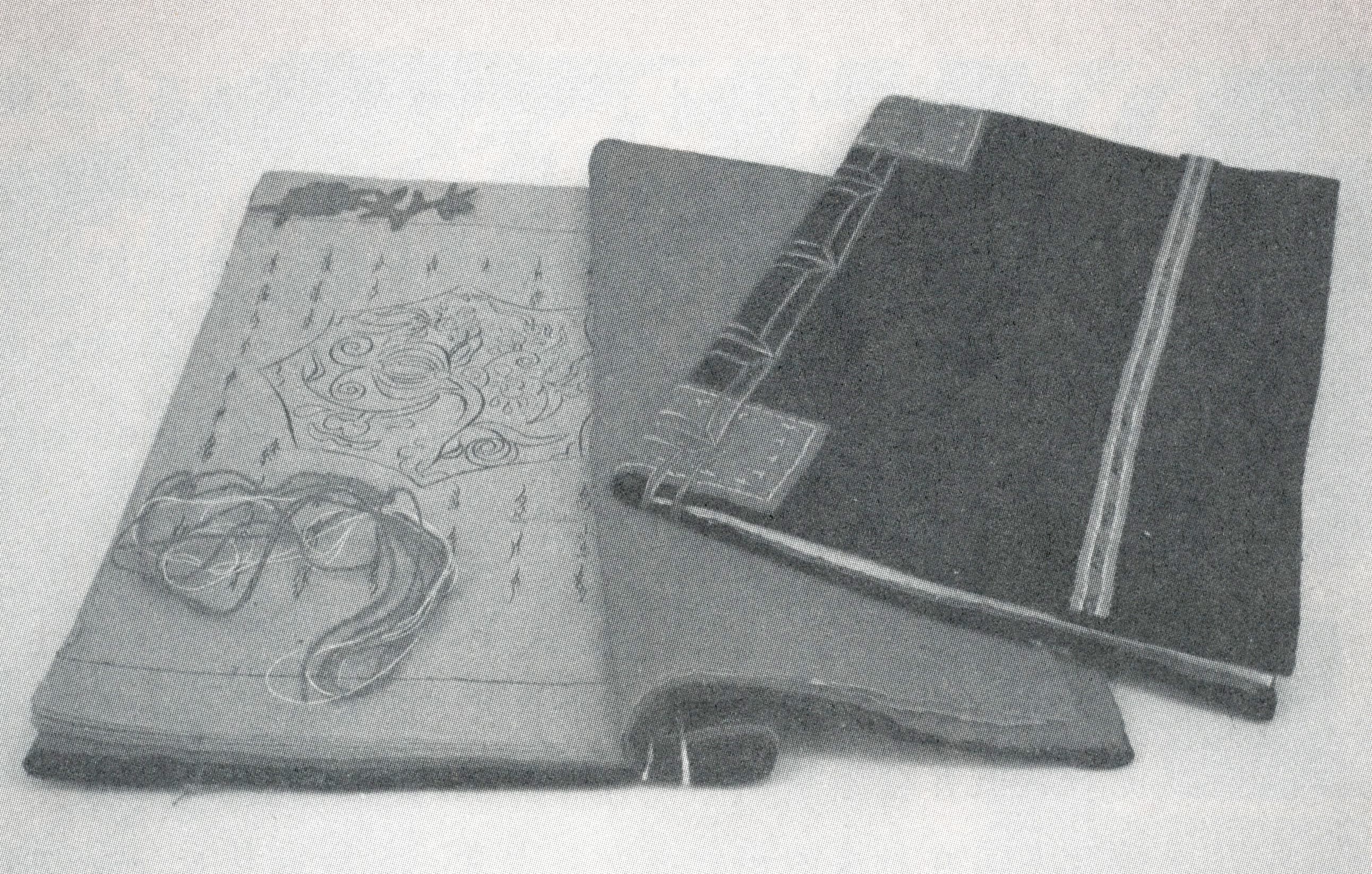

Fan, booklet, wok ash and wood-cut pen, courtesy of Nüshu script Museum

Fan, booklet, wok ash and wood-cut pen, courtesy of Nüshu script Museum

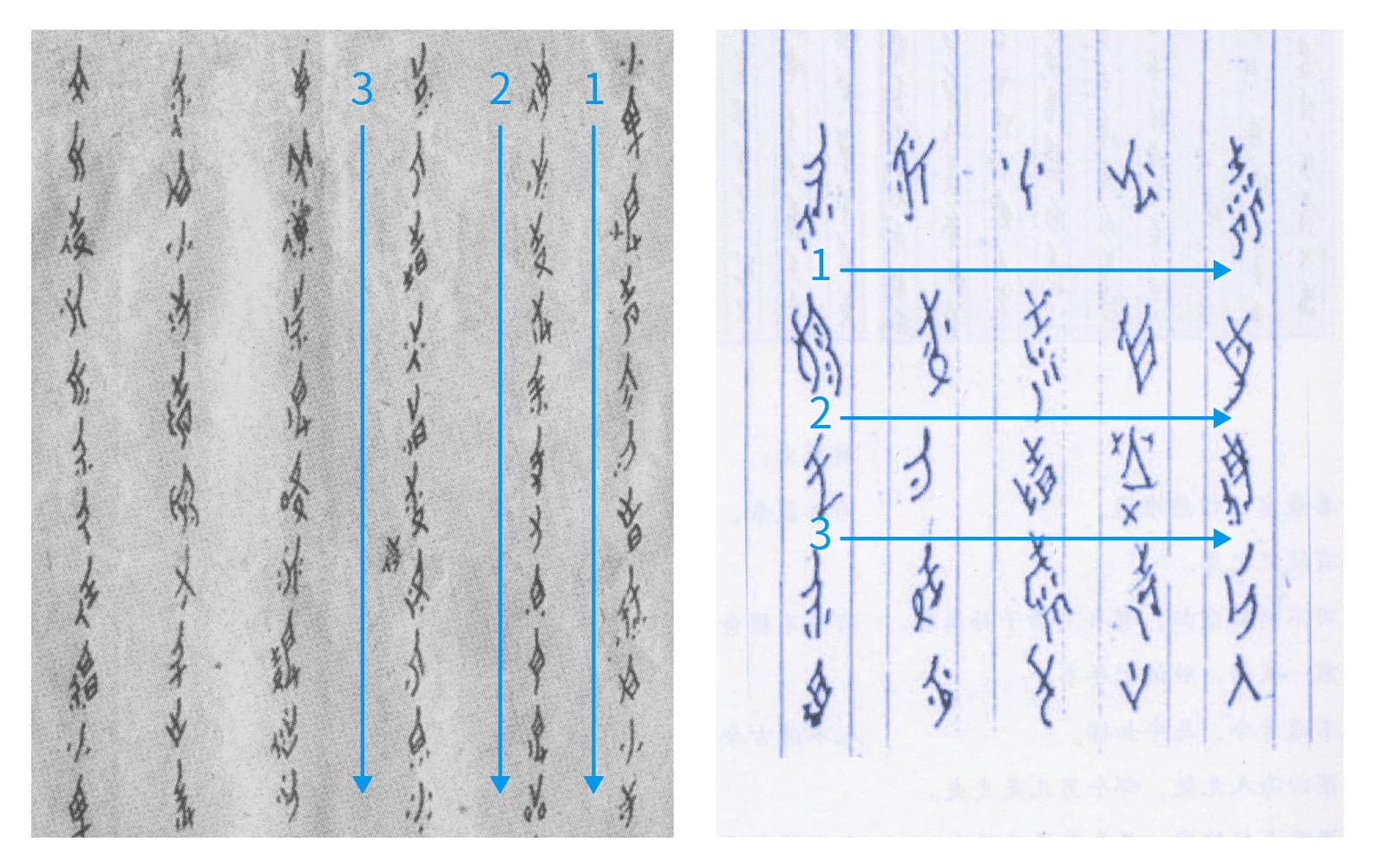

Nüshu texts are set and read just like traditional Chinese: written from top to bottom, lines following from right to left. It can be seen on some texts that the reading direction happens to be characters from left to right, then aligned from top to bottom.

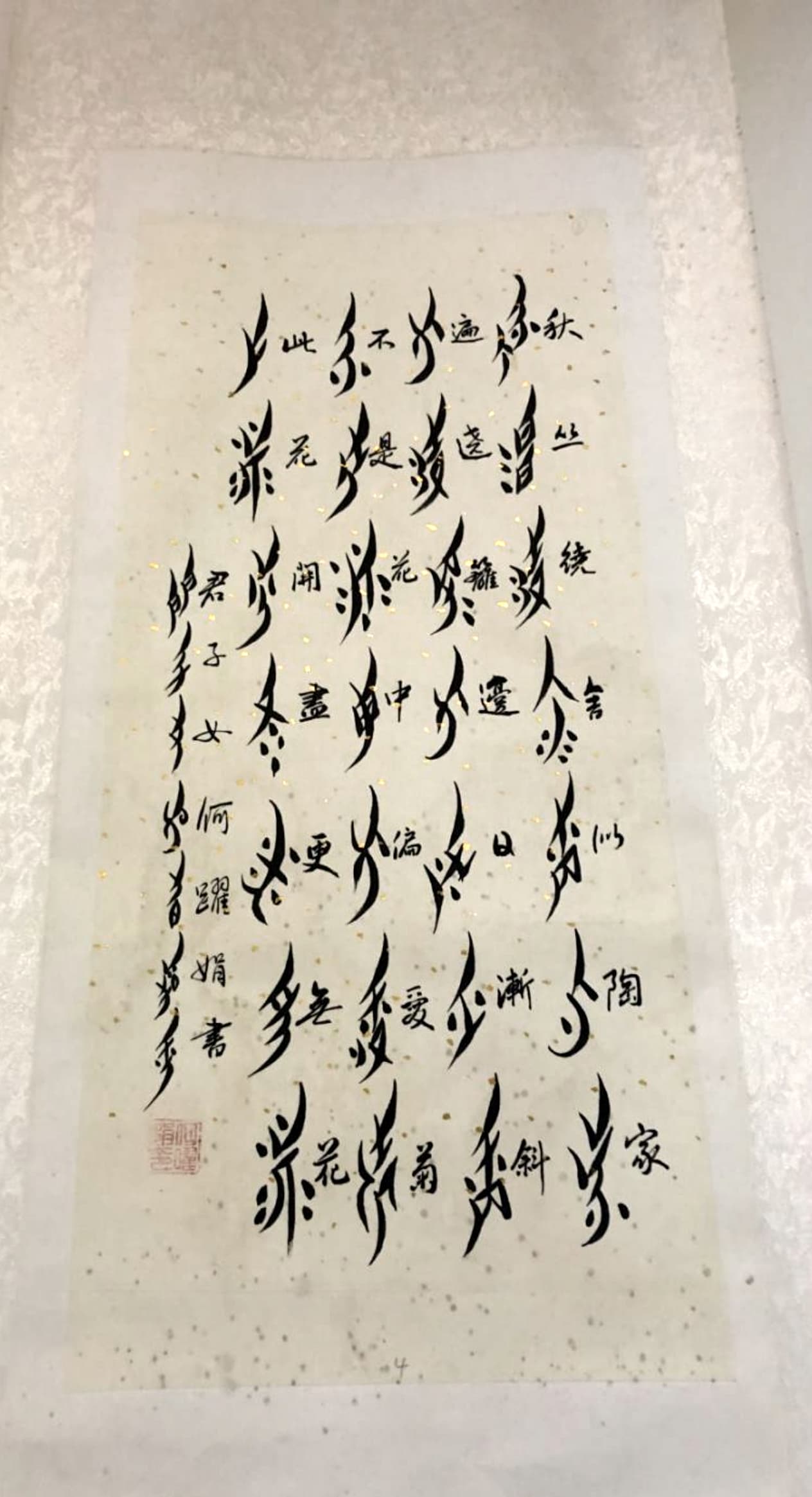

left: anonymous writer, right: 秋夜小坐感 (Lodge in a Temple on the Hill for the Night - 夜宿山寺 by Li Bai 李白) written by Yang Huanyi 阳焕宜 (1909–2004)

left: anonymous writer, right: 秋夜小坐感 (Lodge in a Temple on the Hill for the Night - 夜宿山寺 by Li Bai 李白) written by Yang Huanyi 阳焕宜 (1909–2004)

These features of Nüshu characters give a text written in this script a surprisingly ‘feminine’ appearance, especially when the curves are delicately traced, sometimes exaggerated for an even more elegant feel when compared to squarish and blocky ‘masculine’ Hanzi characters (does a style of writing can bear femininity, masculinity or even neutrality would be an interesting topic of discussion…).

05. How it works

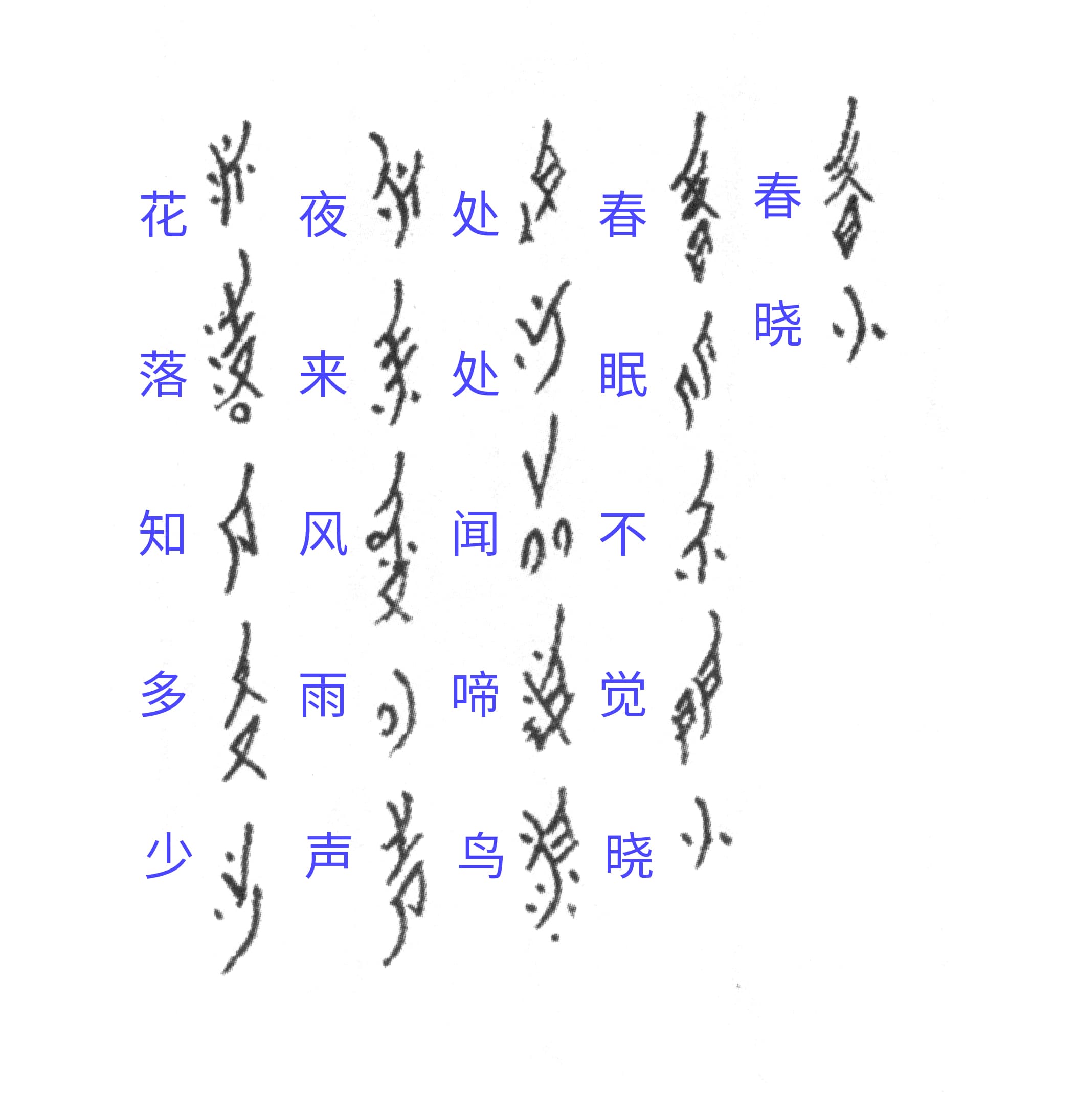

Nüshu has been created and used to phonographically transcribe local dialects, commonly called there as Tuhua. Its system works like Japanese Hiragana or Katakana, when one glyph can be used to transcribe several meanings but with same or similar sound in the dialect. This specificity made the set of characters needed and used drastically smaller than ideographic Hanzi, therefore learning to write Nushu is much more simple and accessible to Jiangyong women who didn’t have access to any education.

A text written in Nüshu can be understood only if the reader knows the dialect and the context. Jiangyong’s dialects are very close to Mandarin, and are different from it only by the pronunciation of the characters. The translation from one language to another can be very easily made glyph by glyph.

Dawn of Spring 春晓, by Meng Haoran 孟浩然, written by He Yanxin 何艳新 (1940 -)

Dawn of Spring 春晓, by Meng Haoran 孟浩然, written by He Yanxin 何艳新 (1940 -)

note: According to Pr Zhao Liming, Chinese Mandarin could easily be transcribed into Nushu (with less than 400 characters) instead of Hanzi characters (which can be up to 106,000 characters according to the Dictionary of Chinese Variant Form - 中华字海…).

Besides all dialects (there have never been a precise number of how many dialects were using Nüshu, some of them are already extinct), the system developed with Nüshu allowed a parallel language called Yayan (雅言 - ‘prestigious language’) or Jiangyong’s common language (江永城关音). Through time, women ended up with a preference for Yayan instead of their own dialect to write down Nüshu texts, teaching this version across Jiangyong, considering it to sound nicer and more suitable to the script. For women in Jiangyong district, Yayan is considered to be the local official dialect.

06. How has it been used

Many legends or stories about the first uses of Nüshu surround the script, but as far as researchers know it from facts and actual documents, it has been mostly used to:

- send messages and keep connexions between villages, between Sworn Sisters, families…

- write down autobiographies with all their thoughts, good and bad, mostly on a Third Day Book (三朝书), a cloth bound with paper pages booklet. It is the most valuable gift offered three days after a woman’s wedding by her mother or other sworn sisters, with the three first pages written with songs wishing happiness to the newly wed. The rest of the book were left blank so that the newly wed wife could write her own texts. These are burnt with the author’s body during the funeral ceremony… This shows how important the book and the script is to the women!

A Third Day Book handbound and written by Hu Yanyu 胡艳玉 (1978 -)

A Third Day Book handbound and written by Hu Yanyu 胡艳玉 (1978 -)

- create songs, ballads and poems (Seven Words Verses - 七言韵文, similar to French Alexandrins), commonly on fans, to be shared and taught to others, sung during gatherings, transcribe popular Mandarin ones into Tuhua

Gentle women (君子女), by He Yuejuan 何跃娟 (with translation in Hanzi in small)

Gentle women (君子女), by He Yuejuan 何跃娟 (with translation in Hanzi in small)

- record festivities (weddings, ceremonies…) and daily facts

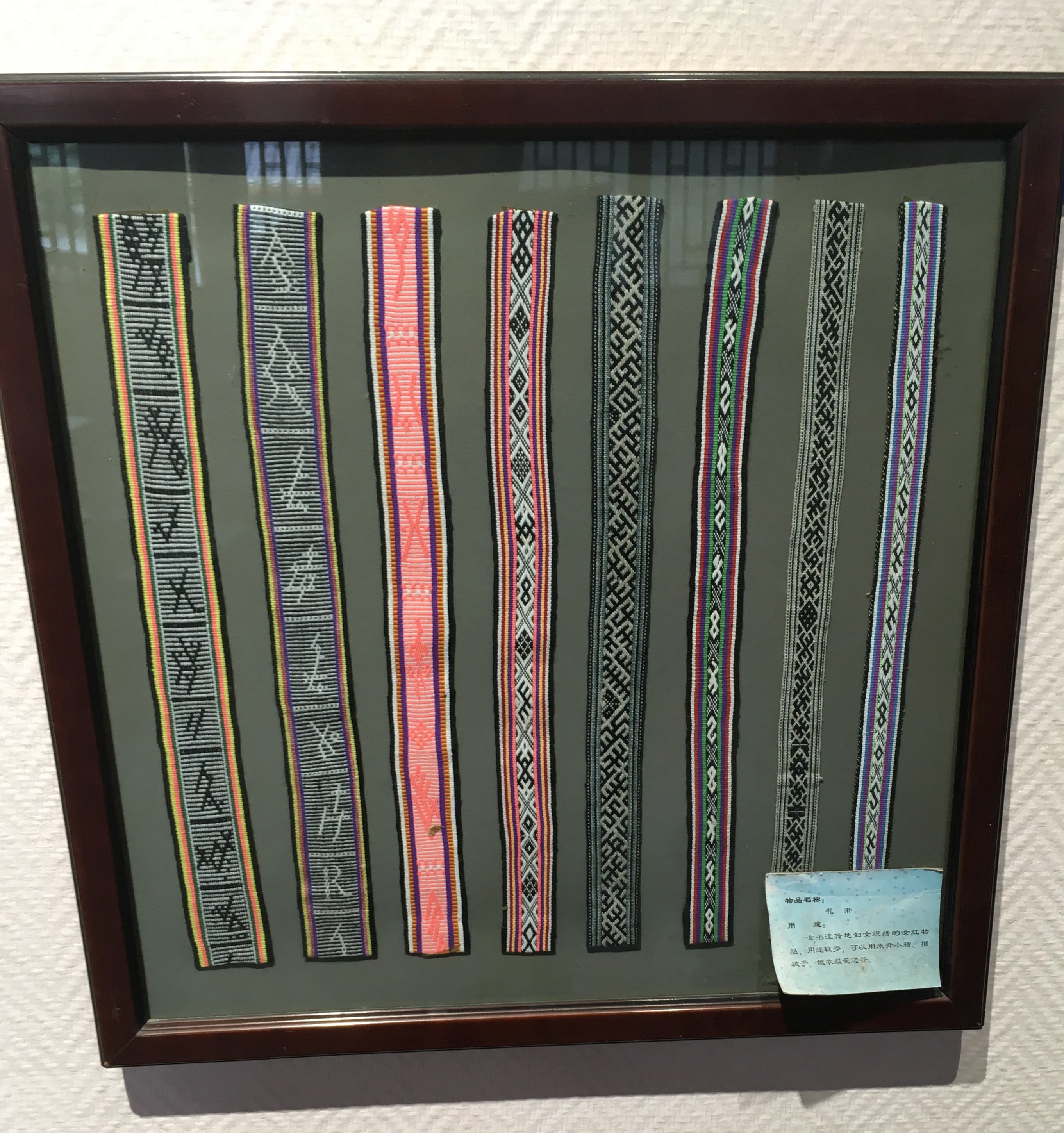

- be also sewn on silk cloths as decorative items or cotton or silk belts (带子花) for newborns clothes, with characters for happiness and health as a lucky charm

Silk belts woven with Nüshu characters in, courtesy of the Nüshu script Museum

Silk belts woven with Nüshu characters in, courtesy of the Nüshu script Museum

Nüshu allowed farmland and mountain village women not only to communicate between each other when they were not allowed to write or read, but also to develop their very own culture.

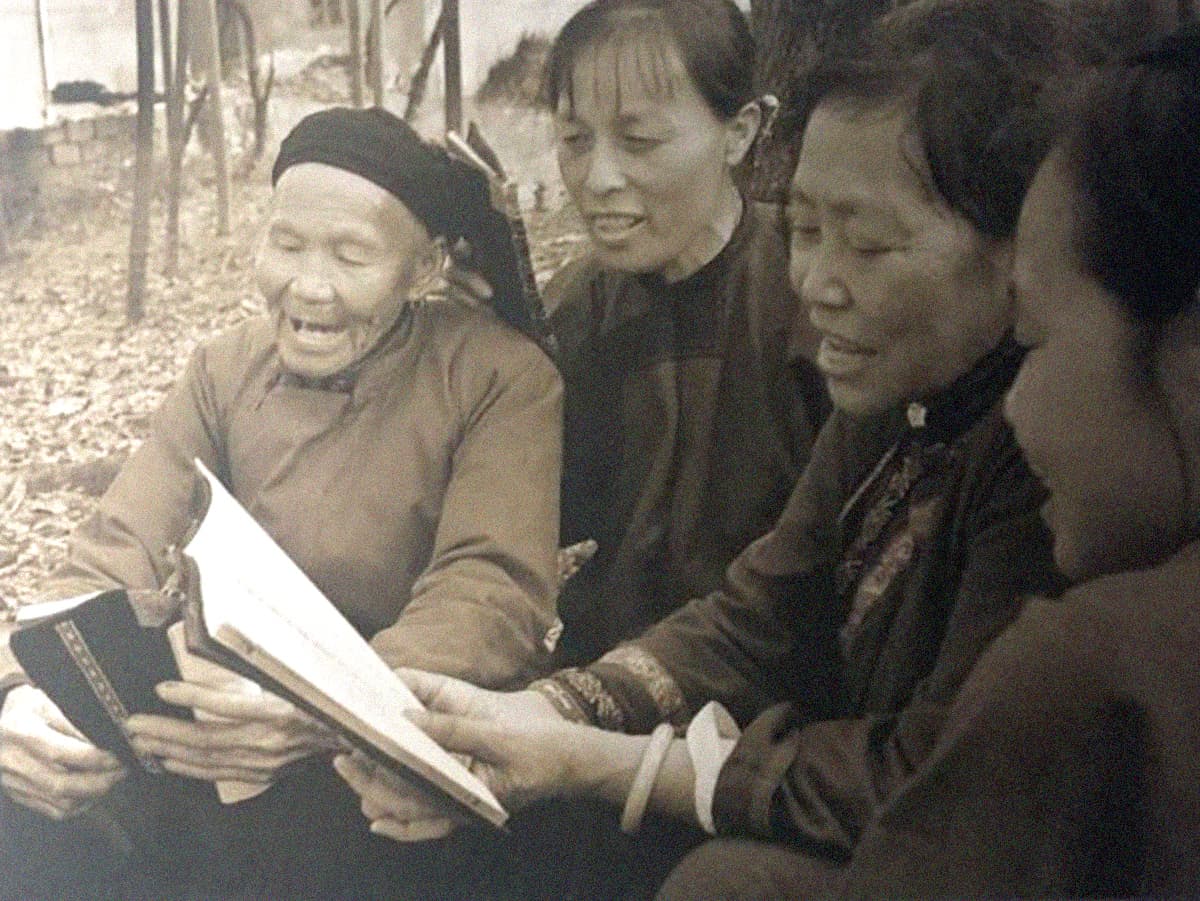

07. How has it been taught

Nüshu has been taught directly from one woman to another(s), generally from mother to daughter(s), without any academic environment or system through the generations. It was very often taught in village halls (歌堂) or at home. Even if there is a common core, each woman or groups of women would bring their own adaptations, styles and preferences to the characters and teach the ones they know to the younger women and girls. To add another layer of complexity, the dialect used in one village can be slightly different in their pronunciation to the one used nearby, which influences the characters used in Nüshu.

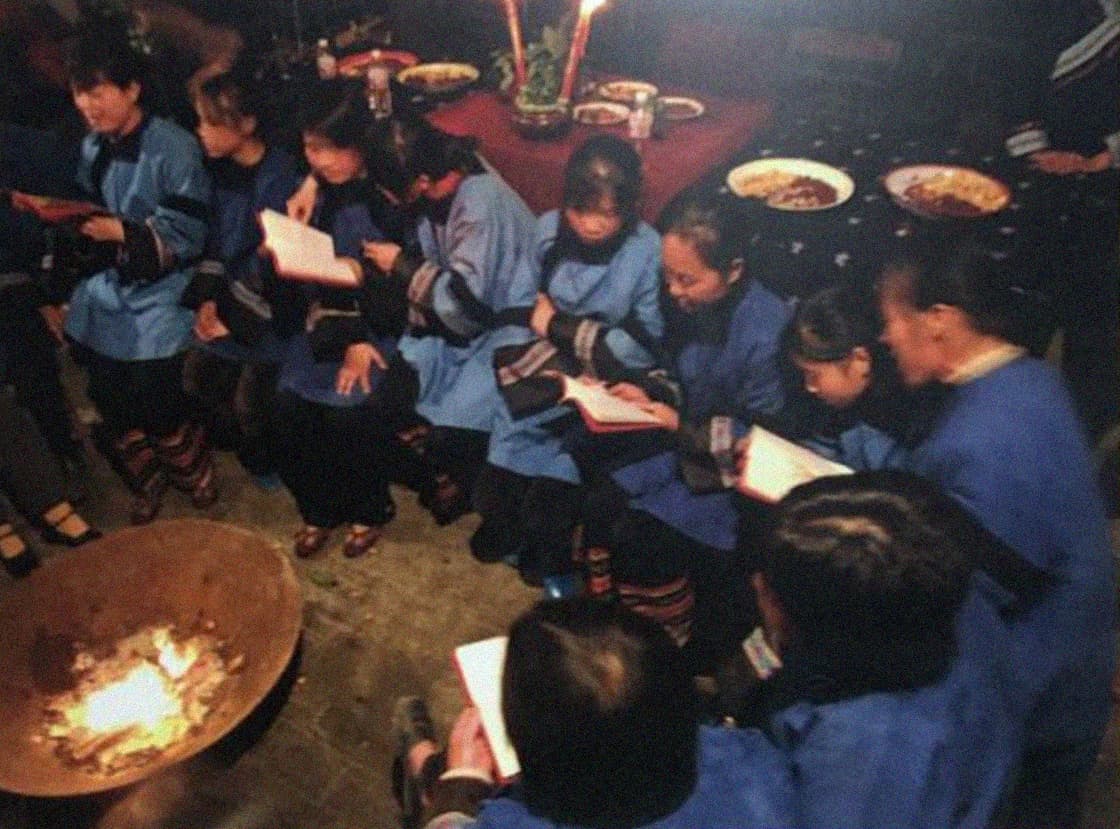

Reading and singing session with Hu Meiyue 胡美月 in center left, courtesy of Nüshu script Museum

Reading and singing session with Hu Meiyue 胡美月 in center left, courtesy of Nüshu script Museum

Group learning session in a village hall, courtesy of Nüshu script Museum

Group learning session in a village hall, courtesy of Nüshu script Museum

These two factors make the standardization of the script very complex and can’t be brought to the same accuracy as Latin script for example. It wouldn’t be quite respectful towards the script’s nature to force it into a static system, but very recently local women who are still teaching Nüshu are very much aware of the importance of keeping their knowledge aligned in the entire Jiangyong area, to keep their culture alive, as united as possible both in their history and in their population.

08. “Discovery” of Nüshu script

Nüshu has always been used openly in the villages. Men could see the script used by women around them without secret but it never caught their attention as they had Hanzi already, and also because it is used by women, and women of a very small area… Until recently!

Between 1950 and 1980, Nüshu started to attract the interest of researchers in linguistics. In 1956, Li Zhengguang (李正光), member of Hunan’s cultural patrimony team, discovered accidentally documents with Nüshu characters while doing a in situ research on Yao ethnic group culture. He wrote the first article mentioning Nüshu in 1957 meant to be published in a national linguistics magazine. But because of the connexion to the co-editor of the magazine to the right wing movement, the article has been cancelled for publication while Cultural Revolution started across the country.

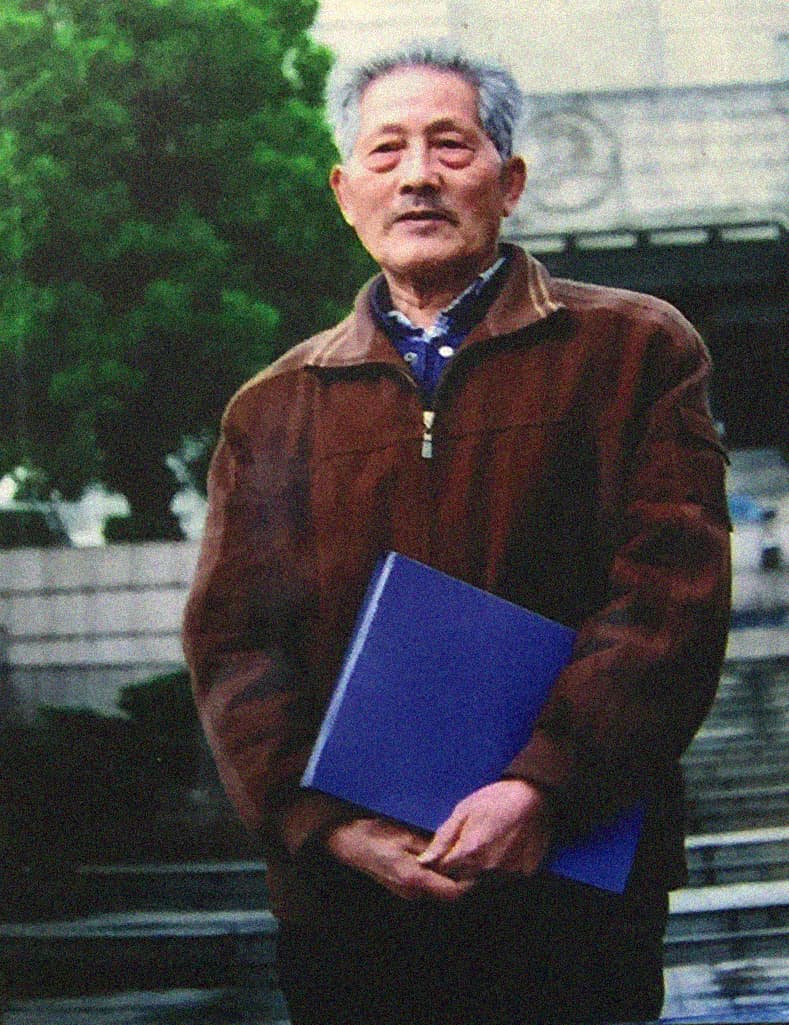

Portrait of Li Zhengguang 李正光 (1937 -), courtesy of Nüshu script Museum

Portrait of Li Zhengguang 李正光 (1937 -), courtesy of Nüshu script Museum

At that time, women who learned and used Nüshu in the original way were already of very advanced age, and the research in the topic was crucial as the original knowledge was on the verge of disappearing. The last woman known to have learned and used Nushu in its traditional way, Yang Huanyi (阳焕宜) passed away in 2004 at the age of 98. That year marked the beginning of the post-Nüshu era (后女书时代).

Portrait of Yang Huanyi 阳焕宜, courtesy of Zhao Liming 赵丽明

Portrait of Yang Huanyi 阳焕宜, courtesy of Zhao Liming 赵丽明

09. How does Nüshu live nowadays?

Nüshu script existence is not so much relevant anymore once Mandarin and education has been expanded across the entire country, accessible to everyone.

Current generations in Jiangyong are fighting to keep this culture alive with demonstrations, festivals, conferences and shows across China and the globe. Even if it is not used at is was originally anymore with education accessible through the entire country and for everyone, local populations are all aware of their precious and fragile legacy. Since a couple of years, local and main governments in the country are promoting the script’s culture, benefitting from its touristic attractiveness, with the creation in 2007 of the Nüshu script Museum in Jiangyong county that organizes Nüshu classes every summer and display not only the script’s history but also local culture and folklore.

Nüshu script Museum village entrance

Nüshu script Museum village entrance

Hu Yanyu giving live calligraphy during a Linguistics exhibition in Beijing, courtesy of Zhao Liming

Hu Yanyu giving live calligraphy during a Linguistics exhibition in Beijing, courtesy of Zhao Liming

Shop signs with Nüshu characters next to their Hanzi counterparts, photo taken by the author in Jiangyong city, 2019

Shop signs with Nüshu characters next to their Hanzi counterparts, photo taken by the author in Jiangyong city, 2019

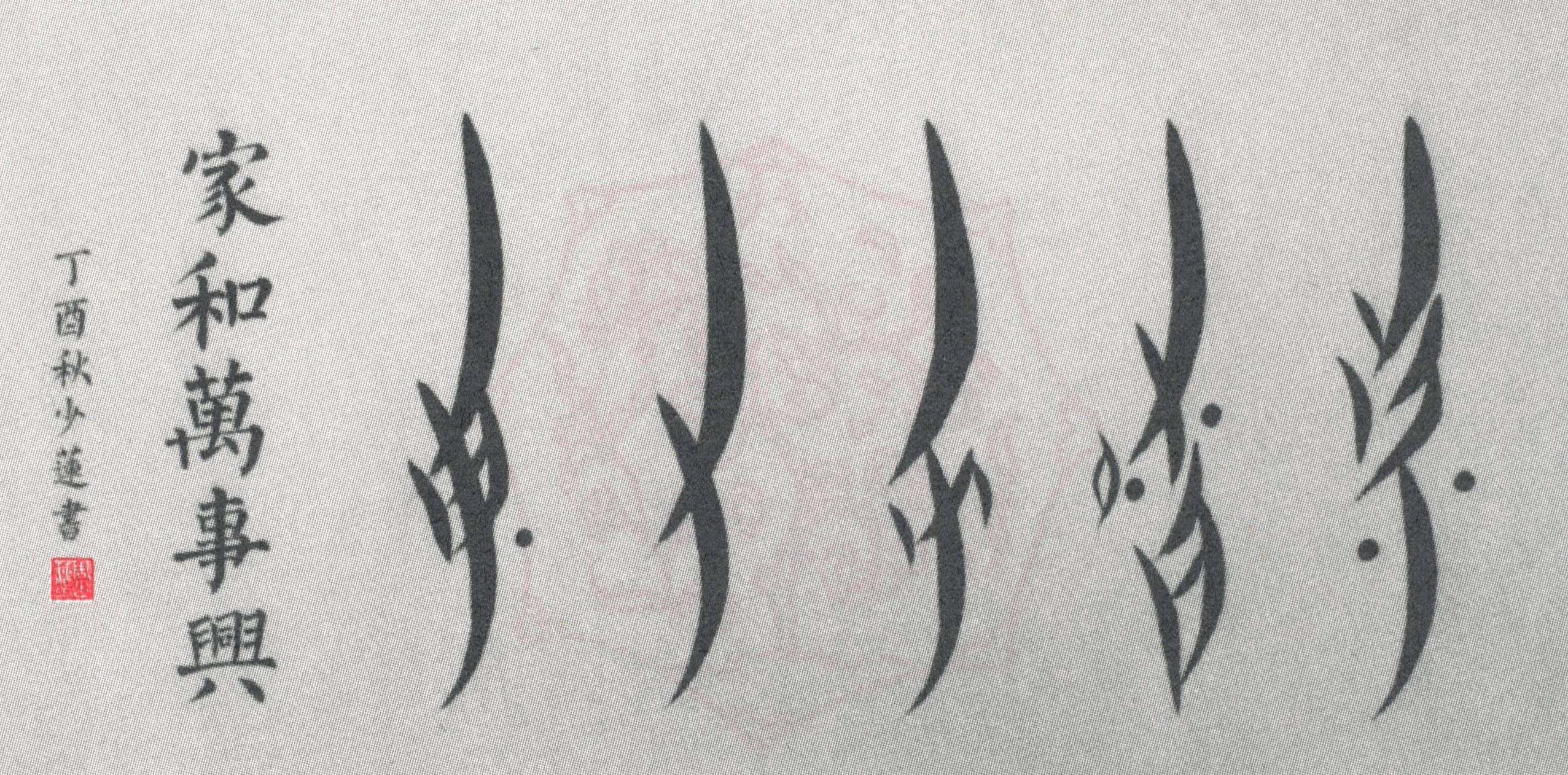

Usage of calligraphic brushes to do Nüshu calligraphy is adopted since a few decades, to write poems, short words or sayings. Displayed like Chinese calligraphy, they show an even more appealing look, a look closer to the calligraphy in Hanzi appreciated and familiar to Chinese people or Chinese speakers.

Translation: ‘All the happiness at home’, by Zhou Shaolian 周少莲

Translation: ‘All the happiness at home’, by Zhou Shaolian 周少莲

Character for ‘Home’ 家, by Hu Meiyue 胡美月,2019

Character for ‘Home’ 家, by Hu Meiyue 胡美月,2019

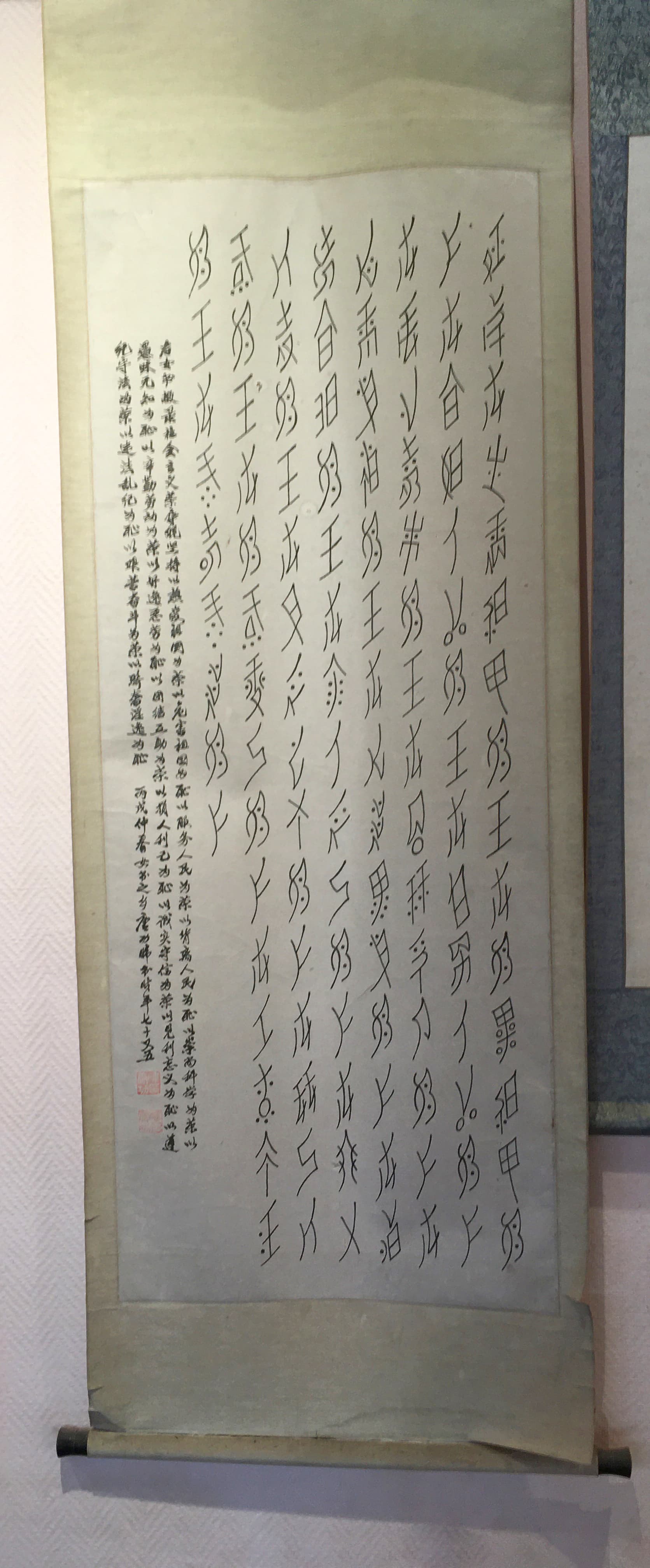

Men calligraphers, researchers and academics also started to write Nüshu, and the masculine feel can oddly be seen even on feminine characters!

Calligraphy in Nüshu by a man calligrapher (author and date unknown), courtesy of the Nüshu script Museum

Calligraphy in Nüshu by a man calligrapher (author and date unknown), courtesy of the Nüshu script Museum

Digital presence of Nüshu script has been brought up to existence thanks to “Professor Liming Zhao and her group of Nyushu rescuing project from Tsinghua University collected and organized around 1,000 original documents written in Nyushu in total and translated 640 readable files from them character by character into Chinese. The scanned pictures of these 640 files and their 220,000-character translation in Chinese are published as the 5-volume Chinese Nyushu Collection by Zhonghua Book Company in 2005.” (extract from Theory and Rules of Nushu Character Unification, Liming Zhao, Sept 23, 2014) In June 2017, the resulting list of 396 selected Nüshu glyphs have been added into Unicode 10.0 version (range 1B170 to 1B2FF). Since then, digitization attempts have started here and there by universities, academics and designers, but none of them have been fully finished and published yet… before Noto Sans Nüshu!

Pr. Zhao Liming (赵丽明博士) is professor in Chinese Linguistics specialised in South Western endangered languages at Tsinghua University in Beijing. Her research in Nüshu started over 30 years ago and is still going on, in collaboration with academics from many other international universities.

Professor Zhao Liming 赵丽明

Professor Zhao Liming 赵丽明

Digital presence of Nüshu will definitely play a significant part in the preservation of the script for the future. Academics will be able to exchange their knowledge much easier through digital communication with consistent content and Nüshu will have a stronger and larger presence on the web and other media with people using or learning the script using the script on modern devices.

The only focus point to care about then would be to keep in a right balance both tradition and modernity to avoid any loss of its authenticity. Which will be quite challenging, as many people and companies see the touristic attractiveness rather than the cultural legacy…

10. Nüshu in Noto Sans family

As already mentioned before (in Chapter 04. The look), I decided to focus on a sans serif version for Nüshu in its digitized version rather than a serif to be as close to the script’s original form as possible. What could be interpreted as serif with Nüshu would be with contrast only. From the last decades, women who are still writing Nüshu promote it beyond Jiangyong county using calligraphic brushes instead of pens (they gave up using bamboo or wood sticks quite some time ago already…), allowing various degrees of contrast in the characters strokes with more or less exaggerated lenghts. Even if this style or writing appeared in very recent years, these calligraphies show an enhanced characteristic of Nüshu glyphs, adding up both writer’s personality and the elegance and finesse that is in its nature, placing the script on an artistic level, just like Hanzi calligraphy.

My connection to the script is quite thin: being Chinese (and a woman) doesn’t make me 100% legitimate to design a Nüshu typeface accurately and naturally, but the will to design it as faithfully as possible made me reaching Pr. Zhao Liming in person and all the women I could meet in Jiangyong, at the Nüshu script Museum, receiving their experience and opinions through the process, look at as many Nüshu texts as I could find, and dive into this peculiar culture. My abilities as a type designer made me care about details, extract the most common features from documents and samples, examine hand written characters and deduce how shapes could be made consistent accross the entire set for a digital font. You can find all the informations collected and sorted in my Process voyage here, feedbacks, opinions and discussions are also very much welcome! 🙃

11. Going there

There are unfortunately almost no English versions or translation as of now, but there is still possibility to reach a local English-speaking guide:

- Nüshu script Museum (女书生态博物馆)

- Visit reportage of a Chinese tourism company

- Closest large cities: Guangzhou, Guilin, Changsha

- Hunan Museum in Changsha, Hunan

References

- 女书诗文佳句 / 赵丽明主编 — 北京清华大学出版社,2019 (ISBN: 978-7-302-52810-4) (no English translation)

- 君子女 / 卢池珠,何裕建,何跃娟 — 名族出版社,2014 (ISBN: 978-7-105-13465-6) (no English translation)

- 什么是女书:赵丽明 ⟪传奇女书⟫, 2016 (no English translation)

- Nüshu: from tears to sunshine, by Cheng Xiaorong, 2018

Other

- Online Nushu Dictionary, 2018-2020

- Nvshu Sans, Designing a Heiti Font for Nüshu, and Ancient Chinese Women’s Script, by Chelsy Wu

- What the world’s fascination with a female-only Chinese script says about cultural appropriation, by Ilaria Maria Sala for Quartz, 2018

Thanks to:

Pr Zhao Liming 赵丽明博士, Hu Meiyue 胡美月, Hu Yanyu 胡艳玉 (directions and feedbacks) ✍️ 🔎 🖍, Stephen Nixon (mastering) 👨💻, Liang Hai 梁海 (advice) 🧭 and of course Google Fonts team! 🙏